Taking a fresh look at the life of Terry Sanford

LAURINBURG — Before the term “progressive” was a political hot take, there was former NC Gov. Terry Sanford.

The Laurinburg native made a name for himself in state and national politics by changing the way political campaigns are run.

He was the first North Carolina gubenatorial candidate to hire a pollster and use a large number of television ads.

Before he was the state’s governor, Sanford grew up in Laurinburg. Born on Aug. 20, 1917, James Terry Sanford was the second child of Elizabeth Terry and Cecil Leroy Sanford. For a while, the Sanfords were business owners in Scotland County, Cecil Sanford owned a hardware store in Laurinburg. But during the Great Depression, the store closed and Elizabeth returned to teaching full time.

Though it was hard for the Sanford family to pay rent on their home, the company that owned the house allowed them to stay, according to the book Terry Sanford: Politics, Progress and Outrageous Ambitions.

Sanford never thought of the family as poor. And he was always a trailblazer. Sanford was one of the first members of Laurinburg’s new Boy Scouts of America troop, then Troop 20 — now it’s Troop 420. Both he and his brother, Cecil Jr., earned Eagle Scout honors in 1931 and 1932, respectively. Sanford said in Terry Sanford: Politics, Progress and Outrageous Ambitions, “What I learned in Scouts sustained me all my life; it helped me make decisions about what was best.”

After graduating high school, Sanford first enrolled in Presbyterian Junior College in Maxton. The school is now Laurinburg’s St. Andrews University. He left the college after one semester and enrolled at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and that is where Sanford developed an interest in politics, decidined in his senior year to major in political science.

After World War II and his Army service ended, Sanford focused on politics, becoming the president of the North Carolina Young Democratic Clubs in 1949.

Proving that he could make difficult choices, Sanford supported UNC President Frank Graham in his bid for a US Senate seat over Willis Smith, who’s family he’d been friendly with. The campaign took on racial overtones because of Graham’s support of civil rights, according to the book, The Rise and Fall of The Branchhead Boys: North Carolina’s Scott Family and the Era of Progressive Politics.

Sanford said in an interview with The University of North Carolina’s Documenting The American South …

“The first straight-out racist campaign that I remember was the 1950 election. The first election I remember in detail where I watched it, took part in it, observed it, from a statewide point of view, although I was in high school, was the 1936 campaign, which had all seeds for this kind of campaign, and yet none of them sprouted. You had Hoey, the conservative old hypocrite, that was the representative of the manufacturing forces. If there was an establishment, it wasn’t much of an establishment in North Carolina. You had Sandy Graham, the clever legislative likable politician. And you had the rebel from out of state, the professor from Salem College, that had been in one term in the legislature, Ralph McDonald, who almost beat him. If ever there was a Henry Howell type situation, that was it. But the race issue, in my memory, never came forth from any side. They never accused McDonald of being racist. McDonald never raised that issue. And that, I think, would justify what Key wrote, even under that stress and strain, when the establishment was assaulted by a carpetbagger in the worst kind of way. We survived those kind of tensions. Then our elections fell back into being pretty much within the accepted framework. That is, the … the North Carolinians of some distinction running against each other, something like this last time. You had Broughton and five other … the race issue never got into that. Occasionally the labor business would get into it, but that’s a little bit different. Broughton-Umstead campaign made a big thing out of Broughton’s support of organized labor. And Broughton handled it by saying he was for all citizens. Even so, I think we kept down some of the more violent differences, just by the nature of the people.”

Sanford was described as the first New South governor by journalist John Drescher. And after his death on April 18, 1998, Duke University, where Sanford once served as president, created the Sanford School of Public Policy and the federal building and courthouse in Raleigh was named the Terry Sanford Federal Building and Courthouse in 1999.

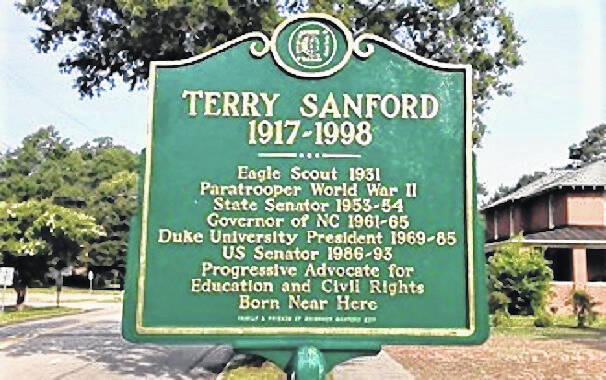

In 2011, friends and family of Sanford placed a historical marker on Church Street in downtown Laurinburg near where he was born.

Cheris Hodges can be reached at [email protected].