On his way back north, the Union

general’s army swung through

this area 156 years ago Sunday

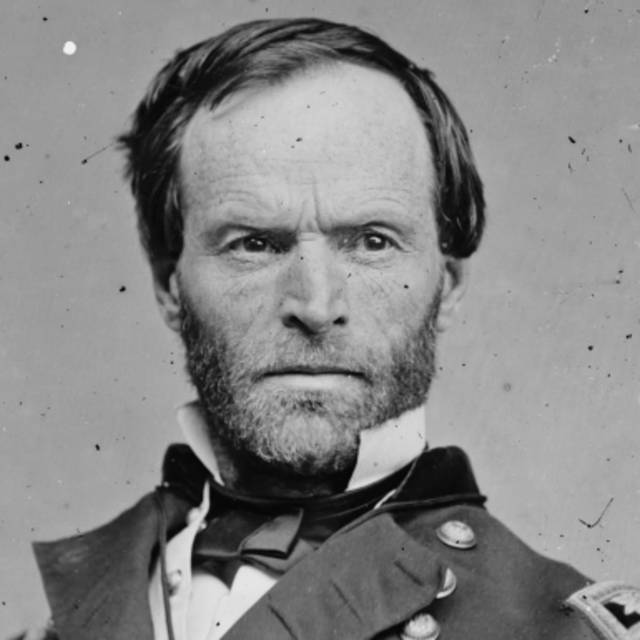

LAURINBURG — On March 7, 1865, Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman led his Union army of approximately 60,000 troops into North Carolina — some of whom found themselves in present-day Scotland County.

Gen. Ulysses Grant, who acted as the commander in chief of US Armies, allowed Sherman to employ any strategy he wished in his efforts to join with the Union forces already occupying Eastern North Carolina.

Briefly following his march to sea, which ended in Savannah, Georgia, Gen. Sherman would devise another strategy for the Carolinas.

Considering South Carolina was the first state to secede from the Union, Sherman took a personal interest in leaving destruction in his army’s path through the state. Sherman’s army would wreak havoc on South Carolina with the intention of demoralizing and punishing the Confederacy.

Once in North Carolina, Sherman’s army would shift its tactic.

“Sherman issued an order that they (Sherman’s troops) were not to burn things that did not have strategic importance once they crossed the North Carolina state line, because North Carolina was the last state to secede from the Union and there was a lot of pro-Union sentiment in the state,” Scotland County historian Bill Caudill said. “Scotland County got off pretty easy in comparison to areas of South Carolina.”

“There are accounts that once Sherman’s army entered North Carolina, there were officers placed at homes to make sure that the troops didn’t wantingly burn, rape and pillage. There was some care and attention given,” added Caudill.

While peregrinating through South Carolina, Sherman’s army torched the towns of Bennettsville, Cheraw and the state capital, Columbia.

Sherman’s army was composed of two main wings, each consisted of 30,000 troops, creating a 40-mile-wide front. A common misconception about Sherman’s army is that they were composed of soldiers from northeastern states like Pennsylvania or Connecticut. The majority of Sherman’s army was composed of Midwesterners from Ohio, Illinois, Michigan and Indiana.

“The history of the term ‘Yankee’ as a derogatory term was based on the lasting impression left by the mid-western soldiers,” said Caudill. “When you see 60,000 people passing through Scotland County followed by captured prisoners, captured by freed slaves that had fallen onto this army, that’s obviously going to have a huge psychological impact on these people.

“The reference to ‘yankees’ as we think of the word was re-imagined at that time to denote Midwesterners such as those who were the majority of Sherman’s army as opposed to those from New England and other parts of what we think of as ‘the North.’ The new term ‘damn yankees’ in local vernacular would refer to folks from the mid-western north as opposed to places like Massachusetts or Pennsylvania.”

As the month of March progressed, the army would destroy railroads, hurting the Confederacy’s ability to transport goods and weapons from town to town.

Arriving in Scotland County

On March 3, 1865, marching “six abreast,” from Bennettsville, Sherman’s right-wing unit crossed the North Carolina state line via present-day Barnes Bridge road. They would travel up to Thompson’s Chapel, the predecessor of Caledonia United Methodist Church, where “musket balls” could be found in the doorway. They would then march slightly west of Maxton to cross the Lumber bridge, to cross the Lumber River at Campbell’s Bridge near the site of present-day Campbell’s Soup plant.

On March 7, 1865, Gen. Sherman and his left-wing unit would enter North Carolina through Gibson, burning as many as 400 bales of cotton. Sherman’s army would spend March 7-8 in Scotland county. Whenever Sherman’s army looked to set up an encampment, they would look for high ground and a good water supply. One part of the army camped on the north side of NC Hwy. 79 at Springfield, while the other would proceed to set up their first encampment at Old Laurel Hill Presbyterian Church. Troops were assigned to serve as lookout in the steeple of the church.

Due to numerous rainy days in the area before Sherman’s army arrived, the swampy roads called for the troops to “corduroy” the road to get all the men, horses and wagons across the swampy region. The troops would strip the church’s pews out and place the lumber on top of the ground to gain traction and get across.

After corduroying their way through Old Laurel Hill Church community, they would pass through Wagram, “where they would use the steeple and goblet mounted on top of the Richmond Temperance Hall for target practice and shot it off, legend has it,” according to Caudill.

While the efforts to demoralize the Carolinas continued, once in North Carolina, Sherman’s army began placing emphasis on “speed and psychological warfare” as opposed to the previous punishing warfare tactics seen in Georgia and South Carolina. The respective wings of Sherman’s army covered seven to eight miles a day. As local civilians saw Sherman’s troops marching, they also saw Confederate prisoners who were captured in South Carolina being held hostage. With strength in numbers, Sherman’s army intended to instill hopelessness, despair and eliminate any sentiment of Confederate success left in the region.

Ultimately, the strategic purpose of employing a two-wing march was to cover more space in less time on their way to join Union forces in eastern North Carolina. The Confederate army, lead by Gen. Joseph Johnson, who were the only opposition to Sherman’s advance, was less than a third of Sherman’s. With the relatively rapid-paced, two-wing army covering a lot of ground they caused the Confederate troops to continuously retreat, minimizing direct confrontation.

While the army still partook in looting homes, farms and businesses for supplies in North Carolina, they were now only interested in destroying things utilized by the Confederate troops. After Fort Fisher was overtaken by the Union, the Wilmington railroad shop was relocated to Laurinburg.

On March 8, “they pretty much destroyed the railroad yard here in Laurinburg,” Caudill said.

Col. Robert H. Cowan, a former Confederate Colonel, was made president of the Wilmington, Charlotte and Rutherfordton Railroad Company. He would move his family to five miles outside of Laurinburg and 20 miles away from Cheraw. Cowan’s daughter, Jane Dickinson DeRorset, provided a first-person account of her experiences with Sherman’s army marching through Scotland County.

Because the Union had heard of Cowan’s activities throughout South Carolina, they showed very little mercy scavenging and looting all things of value in his family home. The army would hold the Cowan family hostage, taking their livestock, personal possessions and their food, leaving them nothing. An individual solider who had joined the Union as a deserter of the Confederacy revealed to the Cowans that he himself was a North Carolinian. The solider would safeguard the family from any harm as the army looted their home.

“As night came on, the guard told my father he must take his family out of that house, for he had to return to camp, and when the rest of the army came up that night he would not answer for the consequences, so after dark we stole quietly through that camp to an old Temperance Hall about a quarter of a mile away,” said DeRorset.

The family would continue to hide out in a Temperance Hall near Springfield with very little resources until all of Sherman’s army had passed through.

After Sherman passed

According to Caudill, “There were a lot of legends passed down. A fair number of the Confederate officers from the region were Masons. The Masonic Lodge was very big in this area. A lot of these men had given their wives the secret Masonic distress signal. A lot of Sherman’s officers were Masons as well. There were some houses along the border area that were sparred because the wives of these veterans had displayed those Masonic distress signals and might’ve been treated a little bit better. They attribute that to the Masonic symbolism.”

A home-fashioned money belt worn by Mary Jane MacLeod Smith of the Wakulla community in Robeson County, was meant to conceal money from soldiers in the hopes they wouldn’t violate a woman, according to the Scottish Heritage Center.

A farm journal maintained by Archibald McEachern of Mill Prong Plantation recounts McEachern’s thoughts on Sherman’s army passing through Scotland County March 16, 1865: “One week today since Sherman and his army pranced through our country. He left desolation and ruin on his track. We can not hear from one word from our great Gen. Lee.”

Parts of Sherman’s vast army would also leave its mark on Robeson County.

Sherman’s army would eventually be challeneged by the Confederates at the Battle of Bentonville, in Johnston County — the largest land battle on North Carolina soil, which resulted in the joining of Union forces under Sherman with those from eastern North Carolina, ultimately preventing a southern retreat from the Confederate forces in Virginia. This all but brought an end to the Civil War.

Jalen Head is a spring intern from The University of North Carolina at Pembroke.