RALEIGH — As state community colleges struggle to raise enrollment, they are looking to recruit more non-traditional students — those older than 25. The push could help lift those students out of poverty and boost North Carolina’s workforce — but only if colleges get it right, advocates say.

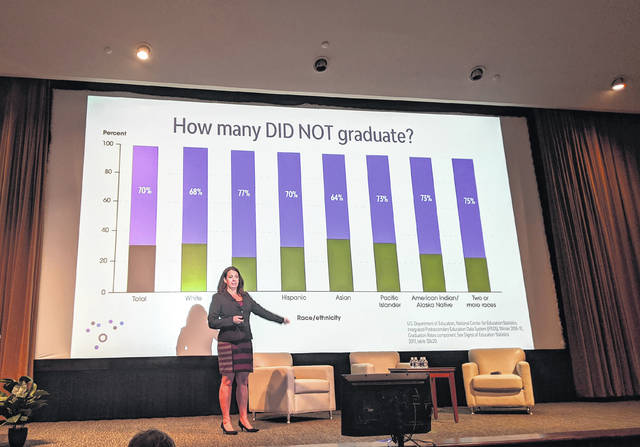

Just getting them in the classroom isn’t enough. Fewer than a quarter of non-traditional, part-time students graduate, and advocates blame the structure of higher education.

“Our part-time system for adults in higher education is perfectly designed to take adults, have them spend more money, and, in four out of five cases, add them to your some-college, no-degree population,” said Sarah Ancel, founder of the consultant Student-Ready Strategies, at the North Carolina’s Adult Promise Symposium on Thursday, Feb. 13, at the Friday Center for Continuing Education in Chapel Hill. “Their chances of success are dramatically lower.”

Community colleges hope to recruit adult students to survive. Community college enrollment has slumped 2% in the past 12 years. Without Wake Technical Community College, the actual decline is closer to 6%, according to the N.C. Community College System.

“Traditional-age students, that pool is shrinking. That’s just the bottom line,” said Denise Pearson from the State Higher Education Executive Officers Association, a national association of state chief executives. “We need to reach those attainment goals, and we’re not going to do it unless we focus on adults.”

But persuading older adults to return is counterproductive unless they actually graduate — and most part-time students don’t.

“Schools, as they try to figure out how to survive, sometimes make adults the simple answer,” said Marie Cini, president of the Council for Adult and Experiential Learning, a national nonprofit consultant. “Their questions are, how do we find these adults, and how do we convince them to come back? Those are the wrong questions.”

Cini argues schools need to ask how they can help adults finish their degrees. Like other advocates, she believes it will require systemic reform.

“They were not built to serve these types of students, policy was not built to support these types of students,” said Scott Jenkins, strategy director at the Lumina Foundation, a private, grant-making foundation. “What doesn’t work well is the idea that you’re going to open up this pipeline of potential students to your institution, and the institution feels no incentive or idea of how do we change to serve these students.”

Some of the changes advocates suggest are simple. They want to abolish caps on transfer credits, and prevent schools from shuffling relevant credits into electives, said Deborah Wright, vice president of Asheville-Buncombe Technical Community College’s program for adult learners.

“You’d be surprised at how many transcripts we have to get for adult students, how many times they’ve attempted to go back and finish,” said Wright. “I want this to be the last time they have to request all those transcripts. We’re going to take as much of that as we can to help them finish.”

Reformers also advise schools to recognize on-the-job experience, like that of a small-business owner studying for a business degree.

“Why would you make that student … take intro to business, intro to marketing, intro anything, when they’ve been doing that work?” Wright said. “That’s what it looks like sometimes for adults to come back and start at zero.”

At the end of the day, the push to streamline credits is about time.

“We shouldn’t give adults the idea that they can take nine, 10, 15 years to get this done,” Cini said. “We need to design models that help them accelerate and get this done in the life they’re in right now.”